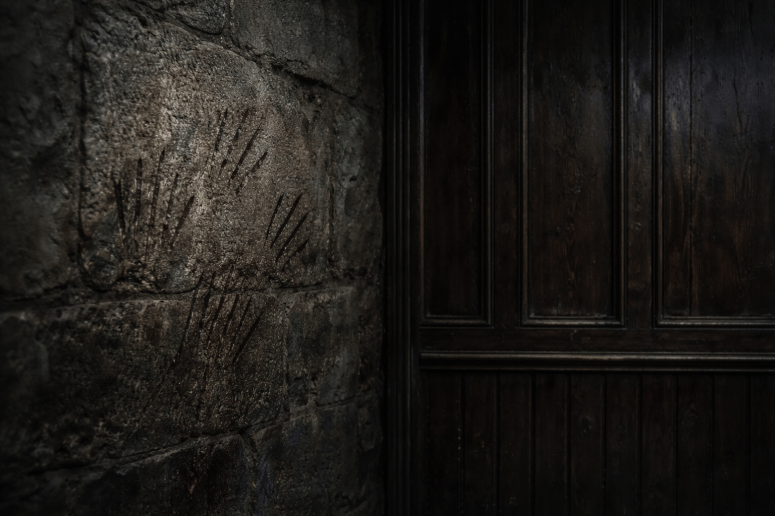

I should begin by explaining that I never truly intended to make notes or journal entries based on an individual I met through the course of my duties at Hooks Cross Asylum. Professionally speaking, such notes would ordinarily be consigned to a file already thick with similar notes, some of the patient’s frantic art, many photographs of her room where she insisted on applying the same scratch marks repeatedly. However, fascination of this patient’s case had me transfixed beyond normality.

The patient to whom these entries all refer was admitted in the winter of 1982, and though I was not then directly responsible for her care, her case came to my attention by reason of a certain persistence which I found difficult to reconcile with the diagnosis assigned to it. I make no claim that what follows will be of interest to those unacquainted with the conditions under which such institutions operate, nor do I wish to suggest that I regarded the matter as anything more than professional curiosity at the time.

It is only because subsequent events have compelled me to revise that view that I now find it advisable to set the facts down in some order.

In the beginning, the case was viewed only as any other would be, and I approached it with the usual professional nature that I would provide any case I was working on. The patient’s statements were taken down, compared with earlier interviews, and found to vary in no material respect. She spoke of the same late afternoon, the same two companions, and the same sound, and though her manner was occasionally agitated, her recollection of sequence and place was unimpaired.

That which truly caught my attention, was not the content of these statements, which was not exceptional by all accounts; but her accuracy in matters that by any reasonable hypothesis could simply not have been known to her. On more than one occasion she corrected me regarding the arrangement of the Mill’s internal gearing; and once interrupted my description with the remark that I had “allowed it to stop early.”

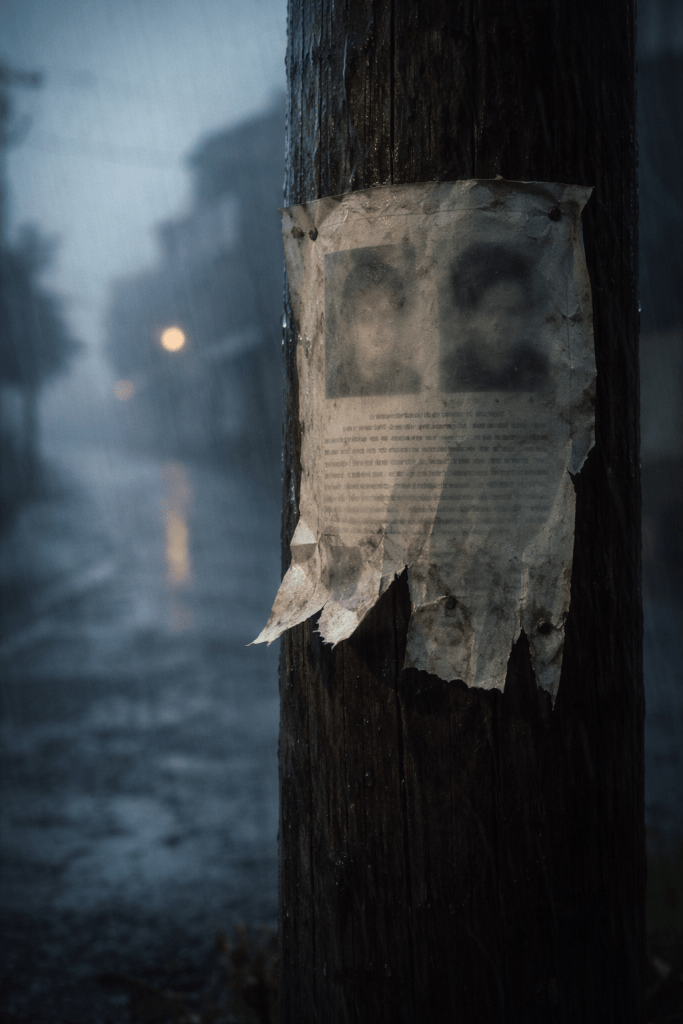

At the time I did not pursue the matter, it was difficult to ascertain if she was displaying anger that might escalate. However, some months later I stumbled upon an article in the local paper which recorded the continued absence of the two boys named in her account. I would have thought nothing more of the article if it were not for its reference regarding the condition of the mill structure at the time. A detail which struck me as being incorrect.

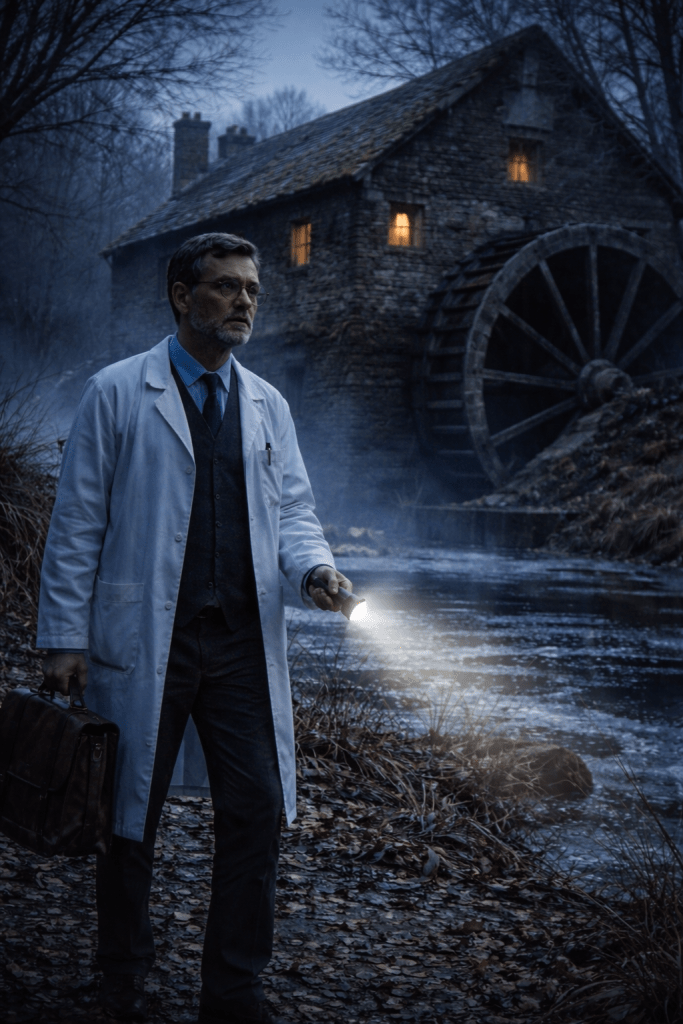

From this point my enquiries extended no further than was necessary to satisfy myself that no error had been made. I took it upon myself to examine local parish records, spoke to a few of the Hooks Cross locals who had memories of the winter of 1982. I even gained permission to inspect the mill from the outside at that time. I did not enter the old building.

Following my visit to the mill I became aware, usually at night and in no more than a moment at a time, of a sound which I took to be no more than the settling of pipes. I mention it only as it was rhythmic, and because I found myself quite without intention, counting it.

During the following weeks I found myself lost in thought on many occasions, drifting into my own world where always the centre of my vision would be the old water mill and that rhythmic sound consuming my mind. The patient began to look at me differently too, and she started to speak of the old mill as if it were a relative, she had not seen in a long time.

Here my natural curiosity for the case grew beyond my professional courtesy to assist the patient to a personal need to understand it in much more depth. Where I had previously only read the assessments made by my colleagues at the asylum, now I read the patient’s own accounts, some of which were accompanied by some very disturbing pictures she had drawn.

The patient consistently recounted the same story throughout her notes, which began as I will now set down:

The three friends returning home at around four in the afternoon, as the sun set rapidly in the winter sky. It was the fifteenth of December 1982, this much I knew from the newspaper cuttings slipped into the case file. That confirmed the three had been out since finishing school that day and were due home by dusk for their dinner. However, it was not until around ten that the patient was found. She was described as terrified and unable to communicate with her family who found her. The families of her two friends continued to look for their children throughout the night with the help of the local police and some volunteers. After nearly a month of continuous searching by many of the Hooks Cross population, there was nothing found that would point towards where the two children might have gone. The search was sadly called off. According to a later newspaper clipping, the children were said to be missing and would remain so as there was no evidence of foul play.

When the search was called off the impact on the children’s families was obviously one of high emotion, but also anger towards the patient, which resulted in several visits where they came aloud to question her. This had a negative effect on her, which meant she then retracted further into her own mind, engaging less and making my job harder. She insisted that her friends were still in the old mill, but police had searched there to begin with and found nothing apart from rotting wood and crumbling stone.

It took me many months to gain her trust and to even talk to me, but now as visions of the old mill filled both my waking thoughts and dreams, I needed her to tell me the truth of that late afternoon in December 1982, where she and her friends had been and where the boys may still be now.

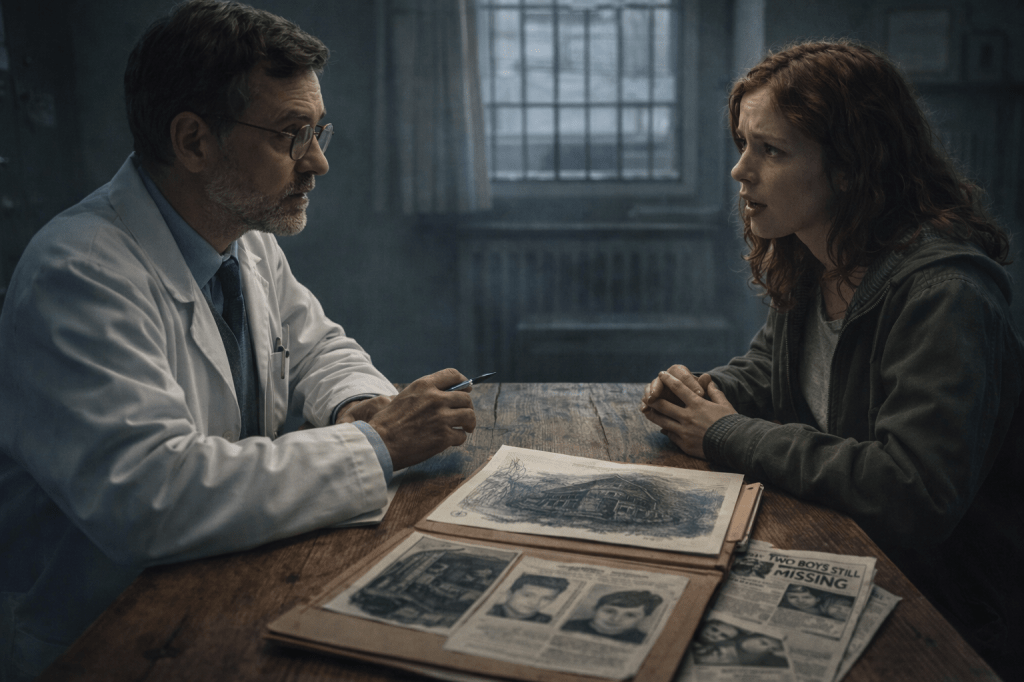

I sat at the table opposite her, placed my tea to my left and opened my journal in front of me ready to make notes. She could not look directly at me to begin with, her gaze constantly towards the floor, but empty, as if no soul dwelled behind her blue eyes.

Showing her the drawings she had made of the old mill, I asked her if Robert Carpenter and Peter Mason were the friends she was with that afternoon. Looking up from the floor, running her index across the water wheel in her picture, then pulling a newspaper article from the case file titled “Two Boys Still Missing After Four Weeks.” She looked me in the eyes and nodded, whispering “Missing.”

With her attention on the matter, I asked if she knew where they were; she tapped the picture of the old mill “the boy.” Still confused, I asked if she could tell me what had happened. Unsure what to expect, I prepared myself to work out any cryptic clues that she may provide, but what happened next, I was not prepared for at all. Not professionally, as it just was not possible; and not personally, as I did not anticipate how connected to this case I had become.

She took a deep breath, changed her posture and simply stated:

“You know, you hear it too. It calls you, as it called me.”

I paused, but for a moment before asking her, “what calls me?” Deep down I felt I knew the answer already. She slammed her right hand down on the drawing of the old mill, “The boy, he has them all.”

Foolishly and trying to regain composure, I asked if she was referring to Robert or Peter. Thinking perhaps one of them was the boy to which she referred. I was of course very wrong.

“The miller’s boy!” she exclaimed.

As the patient appeared more coherent than she had been in many years, I thought it appropriate to try my luck at learning more about the events of the fifteenth of December 1982. Asking her to simply tell me her story so I may finally understand the ordeal that had brightened her into the state that had brought her to our care at the asylum.

She looked me up and down, shifted her position in her chair, took a breath and began to share her remarkable story. What follows is the best account of her experience that I could manage to scribble in my journal as it flowed uninterrupted from her lips.

The account began simply, explaining that she was heading home with Robert and Peter after spending a few hours directly following school at a treehouse that the three had built in the nearby Monks Wood. Something I knew to be true as one of the locals I had spoken to had stated that during the search they happened upon that treehouse. The presence of the three at this treehouse was also confirmed by no less than two of their school friends, according to the local police. Their route home from the treehouse would take them close to the old water mill.

The patient explained that as they passed by the mill, the sun was quickly sinking in the sky, and she felt drawn to the mill in a way that was hard to explain. It spoke to her repeatedly. Then as the three stopped closer to the mill, it was obvious on this very cold afternoon that the mill stream was frozen solid. The great water wheel located on the side of the stone building was locked tight in position. However, the patient explained how she heard the wheel still, but only slightly. Her friends denied this occurrence, questioning if she was okay. It was then that those rhythmic taps seemed to make themselves known to the patient. Her description of those sounds appeared eerily similar to the ones I had also experienced since visiting the mill.

It was then that she heard the calling out of a young boy coming from the old mill. She knew it to be empty, but she could not resist the desire to rush into the mill in search of the boy. Worried about their friend, Robert and Peter followed her into the mill, pausing briefly. She placed her face in her hands in a moment of great remorse and regret, due to the realisation that she had led them into that place. The place from which they would never again return, lost to her and their families.

The door to the mill slammed closed by itself behind the three, she explained, indicating that the mill itself was responsible. Personally, I thought that perhaps a cold winter’s wind had blown the door shut. However, Robert ran to the door right away, frantically trying to open it, but it remained locked shut, forcing the three to head deeper into the mill, seeking an alternative exit.

The sun had now dissolved into the horizon, and the mill was dark throughout, only small shards of light broke through the windows creating small pools of light randomly situated in parts of the mill. The three friends slowly crept through the old mill seeking those pools of light for comfort, as they found themselves cold with fear.

As Robert tightly held the old wooden banister, as the three climbed the stairs, the rotten steps oddly held their weight when really, they should not. Whilst they climbed the stairs, she told me, the beams creaked and moved around them. She told me that the mill appeared new, as if it was no longer abandoned. At the top of the stairs Peter pointed out the initials “R.C.” carved perfectly into the wood. The patient expressed that as they ran their fingers over the initials, they then caught a shadowy movement down the hall from them.

Almost instinctively, Peter found a small stone and threw it down the hall towards the shadow. The stone returned, landing at Robert’s feet. As the three looked up from the stone, they saw the small shadow-like figure of a boy at the end of the hallway. In the blink of an eye, the figure was gone. The three were frozen to that spot for what seemed like hours.

Once the three had gathered themselves together they headed along the hallway, but Robert was different — slightly lost and could not stop himself from touching the wood within the mill. The patient following the grain of the wooden table in front of her, expressed that Robert was then oddly connected to the mill. As they turned the corner at the end of the hallway, the three found a stone wall. Peter was drawn to it, and it was he who found the scratch marks, which were the size of a child’s hands. Robert had no interest, as he became focussed on the wooden panelling opposite to the stone wall. The boys were both now acting increasingly odd, speaking of the mill as if it was a living, breathing entity. Both would tell the patient that the mill needed them all and they should stay with the miller’s boy.

Curious, I asked who the miller’s boy was and why he was there with the three friends. She responded by informing me that the miller had brutally murdered the boy when the mill was still in use. The boy had remained there ever since. I knew that the mill had not been used in well over sixty years at the time the three had ventured into the mill, so the boy of which she spoke could not have been there. Questioning her explanation, she informed me that the boy was now part of the mill. Not entirely sure what she was trying to say, I advised her to continue with her account.

She told me that it was the mill that took her friends. As Peter obsessed with the stone wall, it began to consume him. He appeared to blend into the wall and as he did, he let out the most disturbing scream. The patient attempted to save her friend, at which point she caught sight of the boy again, only to realise Robert too was being pulled into the mill’s wooden wall. Robert reached out for help; she barely touched his fingertips before he disappeared into the cracks in the wall.

Filled with horror she could hear nothing but the turning of the wheel, and everywhere she looked she saw the boy. It would seem at this point the patient simply ran, hoping to somehow find her way out of the mill, which incidentally she did manage to do, but how remains a mystery as her fear was blinding throughout her escape. Perhaps we will never know as that detail is buried and protected in the mind of Leanne Wright.

I struggled for a while to reconcile Leanne’s story, but something resonated with me. And the mill continued to call me for some time after Leanne told me her story.

Eventually the call of the mill got the best of me, the desire to find that stone wall and the wooden panels opposite it became all I could think of day and night. My work suffered and my relationships failed. Which is why I must document this story before I enter the mill myself to find out more. Should the same fate be mine, that was that of Carpenter and Mason, then this journal remains to guide the uneducated. If I do not return with explanations, then Hooks Cross may have more hidden oddities than I was entirely aware of, and they should be explored with caution.

May we meet on our journeys through Hooks Cross.